I woke up feeling a bit "off" today, so I stayed home from church. Having the house to myself for a couple of hours provided the perfectly quiet context for diving into Adolf Deissmann's book, Paul: A Study in Social and Religious History (published in English in 1926).

I have read this book before (well, portions of it) back while studying Bible in university. I don’t readily recall how I felt about it at the time, but I am sure that, given the many other preoccupations that come along with university experience, I have no doubt I thought it was dry or even "boring," and I likely skimmed it more than read it (which would explain my vague memories of its content).

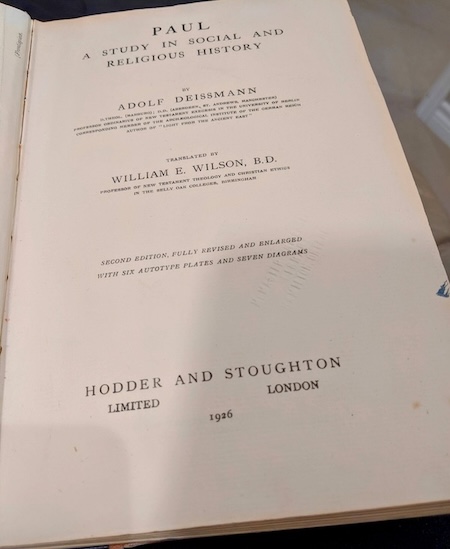

But here I am now, tasked with writing a chapter on Deissmann for a book about modern interpreters of Paul (I wrote on Martin Dibelius for the same series, except it was modern interpreters of Luke and Acts, and I have another one in the works for a book on modern interpreters of the Petrine epistles, where I will write about John H. Elliott). I’m reading the work again as a (much) more "mature" thinker (and person). I’m only a few chapters in as of this post, but I am finding that Deissmann was such a good writer — or, perhaps the translator, William Wilson, helped him out some (I doubt it). Let me give you an example. In the second chapter, Deissmann begins to write about Paul's world. He begins the chapter describing what appears to be one of his own trips from his home to Tarsus, Paul's home city. Upon reading it, I was swept away, imagining being with Deissmann and his travel companions as they traveled by ship and then by train to the place where Paul spent his formative years. I imagined all of us wearing fedoras and leather jackets just like Indiana Jones. Here is an excerpt:

Entering the Cilician plain in March and coming from the interior of Asia Minor or from the west coast one seems to have skipped several weeks; spring is so far advanced. The fig-trees, which in Ephesus and the Meander valley are thrusting forth their first bright green shoots, have here already large leaves that shine delightfully in the sun; the asphodel, which still blooms luxuriantly in April on the Plains of Troy and over the ruined heaps of Ephesus, is already withering in the fields of Soli-Pompeiopolis, a ruined city lying by the sea close to Mersina, and the anemones, which delighted us in their first glory of colour in the Meander valley and at Ephesus, have already bloomed in January on the Cilician plain. Even the poplar of Asia Minor, which with its slender silvery stem enters into sisterly rivalry with the minarets that form the characteristic emblem of Anatolia in city and village, is here further advanced, far further than in Konia or Angora; and by the grey old pillars of Pompeiopolis the luxuriant blossom of the Judas-tree blazes a deep red. Snow scarcely ever falls on that plain. All through the winter the garden supplies the household with its green produce (p. 31).

Such prose is a joy to read. Such prose is becoming extinct.

(added Feb 2, 2025 at 3:30 PM) Here's another stretch of text from Deissmann's book, this time about Paul, that is just terrifically written (read it out loud to yourself [or others]):

And now we see that this man, ailing, illtreated, weakened by hunger and perhaps by fever, completed such a life-work that, as a mere physical performance, challenges our admiration. Just measure out the mileage which Paul travelled by water and land, and yourself try to follow the course of his journeys. You sit, with your viséd pass and diplomatic recommendations in your pocket, in a comfortable modern carriage on the Anatolian railway, and travel in the evening twilight easily toward your destination on the permanent way which has been forced through rocks and over streams by engineering skill and dynamite. While, having already booked your rooms by telegraph, you are carried rapidly and without effort over the pass, you see in the fading light of evening, deep below you, the ancient road, narrow and stony, that climbs the pass, and upon that road a few people on foot and riding donkeys, or in exceptional cases perhaps on horseback, are hurrying along towards the crowded, dirty inn. They are bound to reach it before darkness finally settles in, for the night is no friend to man; the wild dogs of the inhospitable shepherds set themselves raging in the way, robbers are ready to take money, clothes, and beasts, and the demons of fever threaten the overheated and weary in the cold night wind, which is already blowing down from the side valleys (pp. 63-64).

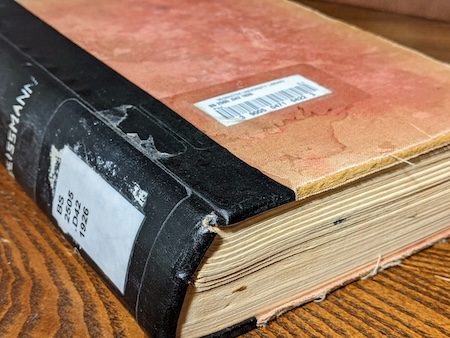

Perhaps I became so enthralled with Deissman's writing because the particular volume that I am reading is an old, well-used and tattered library book that may well have been purchased in its publication year of 1926.

Cheers!