A few (nerdy) thoughts about Jude 12-13

This is a post I wrote quite a while ago, like 3 or 4 years ago. It's just been sitting in my Google Drive for all that time collecting digital dust. It's likely that I didn't post it back then because, well, it's pretty nerdy and contains a fair amount of technical language and jargon--and it's TOO LONG. But I have decided to post it now--and I really resisted the urge to clean it up despite the fact that it needs it. In fact, I'd probably say one or two things differently now than I did then, perhaps even rewriting some of it, but I didn't.

Recently, I was working with one on my Greek students on Prime-Subsequent Analysis (cf. my "Thematization, Topic, and Information Flow") of Jude. When we got to vv. 12–13 (clause 49), he noted—and I was reminded—not only how complex the clause is but also how socially significant it is. I thought I'd jot down a few notes from a sociolinguistic point of view (i.e., Systemic-Functional Linguistic) about it in this post (please note that this is not a fully-orbed exegesis; these are mostly observations about the semantics of this clause that need to be considered when interpreting the entire text).

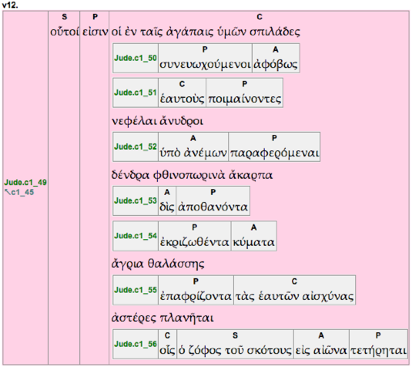

I. First, although it may not be the most complex clause in Jude (compare, e.g., to clauses 5, 77, 88), clause 49, which comprises vv. 12–13, is certainly not the least complex in this short letter of 88 standalone clauses. This clause consists of three basic components: Subject, Predicate, and Complement. However, the Complement is tricky. It's made up of five word groups, and each of those word groups includes fairly substantial and complex modification. For example, σπιλάδες ("reefs"/"stains" [cf. Louw-Nida 21.5 & 79.57]) is modified by two rank-shifted (i.e., embedded) participial clauses ("feasting together fearlessly" and "feeding themselves") functioning as definers and a prepositional phrase ("in your fellowship meals") functioning as a relator. The following is OpenText.org's clause annotation; it helps to visualize the complexity of the clause:

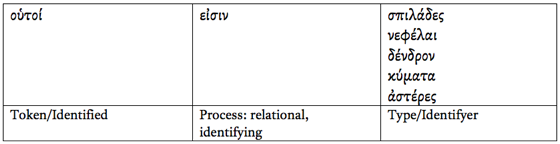

II. Second, from the point of view of Ideational meaning, the clause is an intensive identifying relational clause (cf. Halliday, Functional Grammar [2d ed], 122–29); that is, the clause constructs an Identification relation between οὑτοί ('these') and σπιλάδες κτλ. This relationship is one of Token to Type or, put another way, Identified to Identifier in which Jude presents "these [people]" (οὑτοί) as a specific instance of each of the more general order of the items listed. In other words, "these [people]" are identifiable because they share the same characteristics as "reefs/stains," "waterless clouds," "unfruitful autumn trees that are twice dead and uprooted," "wild waves," and "wandering stars" (see also clauses 65 and 74).

Table 1: Clause 49 analyzed as a relational clause

III. Third, there are a number of things to note regarding Interpersonal meaning.

A. For starters, the verbal Attitude of the clause is assertive, as is grammaticalized by the Indicative Mood of εἰσιν ("are") (cf. Porter, Verbal Aspect, 163–66). This means that what Jude asserts about "these people" with this proposition is, as he sees it (remember that verbal Attitude is the language user's subjective point of view), a fact or an actuality. This particular proposition is classified as a bare assertion, an utterance that is categorical and monoglossic or, in Bakhtinian terms, undialogized. It is not a bare assertion simply because it grammaticalizes assertive attitude, but because Jude does not overtly reference any alternative "voices" or points of view with regard to his proposition. As Martin and White rightly point out, the precise effects that bare assertions have on the dialogistic positioning of the readers is complex; one key for interpreting how such assertions should be read is whether the "disposition of the text is such that the proposition is presented as taken-for-granted or whether, alternatively, it is presented as currently at issue or up for discussion" (cf. Language of Evaluation, 100). The latter appears to be the case. Jude's stated purpose is to encourage the readers to "contend earnestly for the faith" (v. 3), and that he needs to do this because "certain people have secretly slipped in" among them (v. 4). "These people" and their character/behavior—i.e., negatively judging their character/behavior—are the central issue of the bulk of this letter. Thus, it appears that Jude's bare assertion is not concerned with establishing "taken-for-grantedness;" rather, this (and any other) categorical, monoglossically asserted proposition, along with much of its co-text, construes these people as of utmost concern. Consequently, the text construes the readers as not necessarily having the same opinion about these people that Jude does—and that they should.

B. A second note with regard to interpersonal meaning has to do with the linguistics of evaluation. According to Appraisal Theory (cf. Dvorak, The Interpersonal Metafunction in 1 Cor 1–4 ), evaluation gets realized in text through selections from three interrelated, and often interworking, linguistic systems: Attitude, Engagement, and Graduation.

1. I begin with Graduation, since the semantics of this domain often spread out over the other two systems. Graduation is the system of scaling force or focus; that is, "grading according to intensity or amount, and . . . grading according to prototypically and the preciseness by which category boundaries are drawn (Martin and White, Language of Evaluation, 137). When this system is called upon to scale attitudinal (more on this below) meanings, they construe greater or lesser degrees of positivity or negativity; when drawn upon to scale engagement meanings (more on this below), they construe the language user's intensity or degree of investment in the value position undergirding their utterance (cf. Martin and White, Language of Evaluation, 135–36). Examples in English would include things like "He's pretty ticked off" where "pretty" mitigates the force of the attitudinal quality "ticked off." Or, "Now that's a real Dad!" where "real" sharpens focus on the technically un-scalable category "Dad." A simple example in Jude is πᾶσαν σπουδήν (v. 3), where "eagerness" (σπουδήν) is upscaled (force) by "great" (πᾶσαν) [+FORCE: QUANTIFICATION]. Another way to add intensity is repetition or, as is the case in clause 49, to "pile on" descriptors—and, even more by employing, as in this case, metaphor (cf. Martin and White, Language of Evaluation, 144–45, 147–48): "reefs/stains," "waterless clouds," "unfruitful autumn trees that are twice dead and uprooted," "wild waves," and "wandering stars." Jude is clearly maximally invested in his opinion of "these people"; clearly, he doesn't like them.

2. The system of Attitude has three subsystems. Affect encompasses those meanings people make via positive or negative emotions or feelings. Judgment construes one's positive or negative attitudes (both in terms of social sanction and social esteem) with regard to another person's character or behavior. Appreciation encompasses those positive or negative evaluations of things (including abstract things like ideas, etc.). In clause 49 (and, frankly, in much of Jude's letter) negative judgment is foregrounded. Each of the metaphors Jude uses to characterize those who had infiltrated the group signal negative judgment (for a good summary, cf. Moo, 2 Peter, Jude, 256–58). In fact, two of the metaphors (σπιλάδες and κύματα ἄγρια) may derive from pagan traditional material (cf. Charles, Literary Strategy in the Epistle of Jude, 162–63). Regardless of their origin, Jewish or pagan, these metaphors represent a negative appraisal of the behavior and/or character of those who had infiltrated the church. These judgments pertain to a mix of social sanction and social esteem. For example, if σπιλάδες may legitimately glossed "(hidden) reefs" (cf. NASB; Moo, 2 Peter, Jude, 258–59) and the intended meaning is something like "dangerous hazard" (cf. NJB), the metaphor could realize a negative judgment of social sanction with regard to veracity (="these people" are dishonest, devious) or a negative judgment of social esteem with regard to tenacity (="these people" are disloyal, inconsistent, unfaithful). Either way, they're bad.

3. Finally, language users select options from the system of Engagement to position their own voices/value positions vis-a-vis other voices/value positions that comprise the heteroglossic backdrop (cf. Bakhtin on heteroglossia and dialogism) against which the language user is speaking/writing. Basically, language users to this in order to show alignment with or distance from other points of view on the subject matter about which they are speaking/writing. Earlier in this post, I mentioned that clause 49 in Jude is a bare assertion. That means Jude does not overtly reference any other point of view with regard to the proposition he makes about "these people." This makes the assertion "monoglossic" or "undialogized"—it is as if no other alternative point of view or opinion even exists, let alone matters. Jude privileges his point of view by, essentially, ignoring any others. This, in terms of reader positioning, is hugely important. It portrays a readership that may or may not agree with him, and those that do not had better because his is the only valid point of view.

IV. Let me close this post (finally, eh?!?) by describing the social action that appears to be intended with this clause and, frankly, with much of Jude. In their article, "Conflict in Luke-Acts" (The Social World of Luke-Acts, 97–122), Malina and Neyrey aptly use a social model of conflict and labeling theory to analyze the trial of Jesus in Luke. You can get the full details of the model there; here, I will focus on labeling. Labeling is essentially "social name calling," and its social purpose is to accuse another or others of deviance or, if the labels are positive, to give others prominence. Deviance "refers to those behaviors and conditions assessed to jeopardize the interests and social standing of persons who negatively label the behavior or conditions" (Malina and Neyrey, 100 [italics theirs]). Negative labeling, then, is a means of accusing people of violating the shared norms of the group or larger social system, assuming that the labels are negative. Here in clause 49, Jude labels "these people" as deviants, as those whose values jeopardize the shared values of the believers. So, Jude's purpose—his intended social action—appears to be to accuse these people who have snuck in of violating the values shared by the group of Jesus followers. This is done for moral purposes, viz. to distinguish what is evil and wicked from what is good (cf. Malina and Neyrey, 100), and to position the readers to feel the same way about these outsiders and to avoid them—unless, of course, they undergo a conversion (on conversion, cf. Nock's classic work Conversion) in which they adopt the values of the Jesus followers.